I crossed the hall to Momma’s bedroom. A cotton puffer jacket rested on a chair. I hesitated, then opened the closet. Rows of black velvet hangers. There it was: a blonde mink pea coat with a suede sash. One she had owned for forty years. Rarely worn, not her favorite, but somehow it survived four houses and two states. Somehow it had always escaped the bags of SafeNest donations she packed every six months and left by the curb.

She slipped it on. I slipped mine on. Our elbows linked.

Two coats, two women, stepping outside into a living snowglobe. No plows, no green “Keep Milwaukee Beautiful” salt chests. Just desert silence. Flakes dusting our lashes and melting on our tongues like unleavened communion wafers.

We strolled arm in arm, laughing like schoolgirls, warm in each other’s presence.

February 1993 - Philadelphia

I ignored the “Do Not Cross. Go Around” yellow caution tape that partially blocked the scaffolding on Chestnut Street after a deep snowfall. It was a tiny stretch – six yards at most. Rerouting pedestrian traffic to a roadside path seemed rather extreme. This was Philly; cars didn’t yield worth a damn in the best of weather. Besides – I’d be quick.

A mini-avalanche from above hit my head and knocked me flat, muffling my “WTF?” screams. Just powder, not ice. Three men across the street pointed to the signage, back to me again, and doubled over with laughter. Half chuckling and half humiliated, I stood up, brushed off, and went about my business.

I had my warning. It struck like lightning and flattened my arrogance in an instant.

June 2023 – Milwaukee

The plan was for Auntie Clara – my mom’s lifelong best friend and fellow Delta soror – to accompany me to Momma’s funeral, but she had injured her back and was still on the mend. So I went to her house after the service.

We sat on her sofa with her daughter Kim for two nights straight, catching up over hugs and plates of barbecue.

She shared memories of my mother, both silly and serious.

Like channeling Snow White:

“Her parakeet, Petey, would fly straight to her shoulder, content as could be – and glare at everyone else in the room with his beady little eyes.”

Or dressing like Mary Tyler Moore:

“The Black Mary Tyler Moore,” she corrected. “One windy fall morning I pulled into the office lot, and there was your mom stepping out of her Oldsmobile Cutlass: A-line turtleneck sweater dress, matching hat, curls peeking out, fresh lipstick. I thought, she’s gonna take off that hat, spin around, toss it in the air, and flash that little lipsticked smile right in the middle of the lot. Then I thought, nope. Not the Black Mary Tyler Moore. She wasn’t about to ruin that rollerset before 8 a.m.”

They had each other’s backs, from their childhood friendship through the evolution of their careers at MPS as principals, administrators, and board members.

Momma advocated for Black teachers and students, but constantly fought against systemic efforts to block her autonomy.

“Your mom was directly involved in overseeing programs for children enrolled in public schools, especially Title I and other federal initiatives. She was promoted, given new titles, but others tried to strip her of authority - moving her, renaming her roles, taking away real decision-making power. She kept working for Black children even as the system tried to box her out.”

Auntie Clara fought against the unwritten rules limiting Black teachers per district.

“At that time you could have one, maybe two Black teachers in a white school, and limited numbers of Black teachers per district. It wasn’t written anywhere, but it was enforced like law. We fought to break those rules, but every appointment came with a fight.”

When Momma’s promotion was announced, her car was vandalized in the parking lot.

Then the anonymous phone calls came: men tied to the teachers’ association, trying to bar Black teachers. Every night, every fifteen minutes or so.

Auntie Clara ramped up her efforts by planning an out-of-state meeting with California legislators. And on the evening before catching her flight, her garage was firebombed.

“They said, ‘Call it off. Call it off.’ When I refused, they burned down my garage. They traced accelerants from the garage to my kitchen windows. The firemen told me it was professional. That was the cost of insisting that Black children deserved principals, teachers, and curriculum that reflected them. That’s the kind of danger we faced for simply demanding equal footing.”

She stood in her nightclothes comforting her daughters while firefighters battled flames meant to erase her.

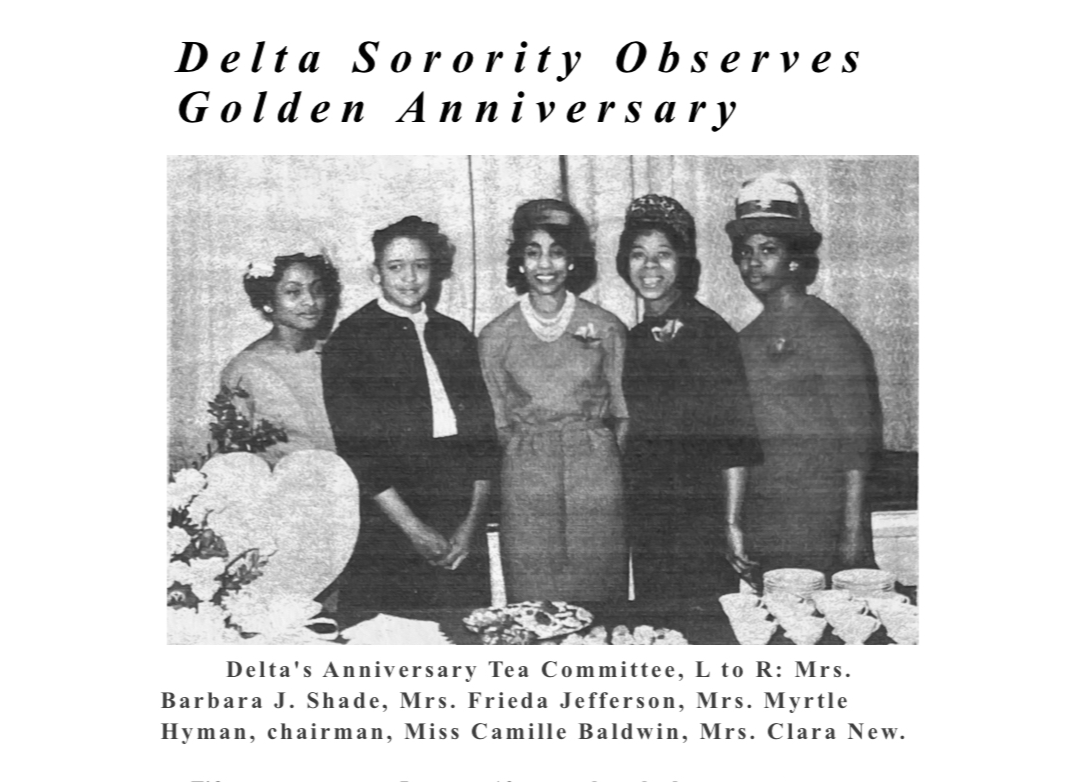

Momma always downplayed the danger in front of us. Her phone conversations were hushed, sotto voce, spoken in code. I strained to catch bits and pieces. She could spin why we had a loner car for so long, or why there had been a fire in Auntie Clara’s garage. But she couldn’t explain away the time Aunt Myrtle – then serving as an assistant principal – was physically assaulted in a classroom.

She came to our house a few weeks later, her jaw broken, rewired, her teeth replaced. The sight of her injuries made everything click. I finally understood: Aunt Myrtle, too, had stood in the line of fire simply for showing up as a Black woman in power.

July 2023 – Henderson